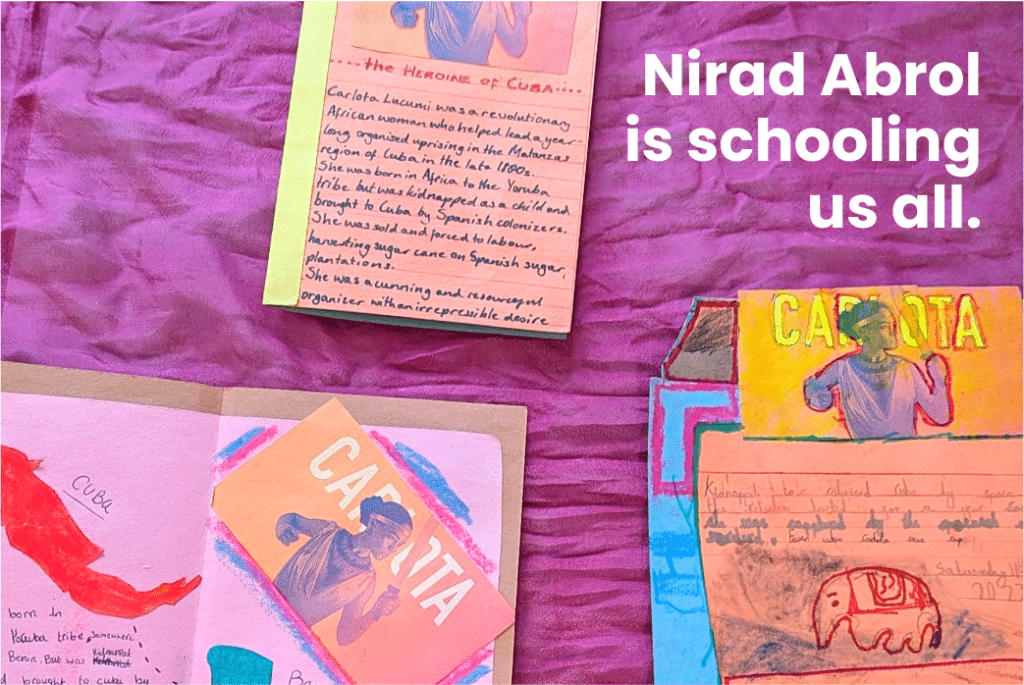

With funding from Challenge and Change, Nirad Abrol is enriching a new generation of young people through pan-African supplementary education.

It’s safe to say that Nirad Abrol is as well connected an activist as they come. This is, in part, the result of the many enquiries he is preoccupied with, from how we can better engage educators in challenging OFSTED and PREVENT, to how organisations can recover if they’re in conflict with their Trustees. Marches to working class music venues, access to radical posters and books, the differences between the NGO sector in Jamaica and Haiti: these are just some of the things that are on Nirad’s mind. He is preparing to visit Ireland for the Easter Uprising commemorations; shortly after, he will head to Glasgow for May Day celebrations.

“Labour history is very visible in Glasgow, even more than in Cardiff. We generally don’t learn anything about Wales; maybe something about castles and where water comes from,” he observes, sitting at ease in Dyddiau Du, a NeuroQueer community library in the southern Welsh city of Cardiff. “But Wales has its own participation in British labour and its own specific national history. That’s why travel is important because there’s all these intersecting histories and I’m trying to keep track of it.”

Immersed, too, is Nirad in learning from radical movements around the world. He’s exchanging ideas with an artist in Chicago who’s delivering an abolitionist school programme; he’s learning about the histories of Egypt and Sudan from a fellow activist; he’s part of planning a residential to which people from the USA, Panama, Palestine and Burkina Faso have been invited.

Nirad needs more time. He teaches at the Children of the Sun Supplementary School in Perry Barr, North Birmingham, and is the Project Manager for the School with Roots Programme at Maslaha. He is an activist with organisations including Jamaica LANDS and No More Exclusions, at which he works to develop political education for young people and support with parental advocacy. With funding from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, Nirad conducts vital research and produces teaching materials about the 1981 uprisings in England.

“I guess I could explain my work in two quotes,” says Nirad. “One is by Che Guevara: ‘society as a whole must become a huge school’, and my approach to the work comes from [Stuart Hall’s] Policing the Crisis which expresses that the Black working class in Britain is part of two different but intersecting histories: the history of labour in the Caribbean and the history of the working class in Britain.”

With support from the Challenge and Change Fund, Nirad has been able to expand his work with Children of the Sun Supplementary School, providing lessons, activities and materials that enable young people to explore their heritage and receive educational support.

“The root of my approach is my interest in pan-African supplementary schools,” explains Nirad. “I was interested in engaging with them but also creating material. Now, that’s something the project has developed into but, really, at the root that’s probably what I was searching around for. There’s a need to create resources exactly for this, so that when people come to that space, there’s a reason that they’re there.”

“How do we introduce young people to a form of education that isn’t just about getting them to change themselves for the system?”

The UK supplementary school movement is believed to have started in the 1960s, when parents, teachers, activists and community leaders worked together to create volunteer-led Saturday schools at which Black children could learn about pan-Africanism and Black history as well as other core subjects.

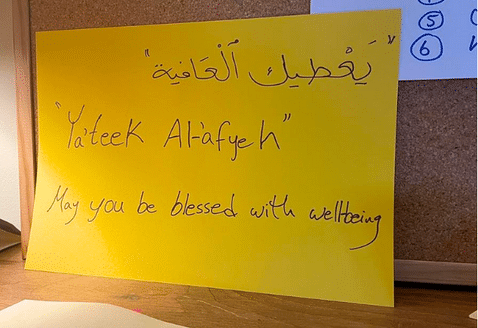

“Over six months we’ve done twelve sessions that I’ve led which have been about history,” says Nirad. “Some have been really fun and some didn’t end up working, around mask making, around yam festivals. There are still kids I think who are really shy to share, even when they have really good points, or who are very quick to close up when someone says, ‘you haven’t done that right’ because that’s what’s expected in school: you have the right answer or you have the wrong answer. That’s not what I’m trying to achieve in this space.

My focus on the project is to examine how we introduce young people to a form of education that isn’t just about getting them to change themselves for the system, so what you’ve seen about racial linguistics when OFSTED inspectors observe if children are talking ‘King’s English’, which is about seeing how people are adapting themselves to a racist, sexist system.”

A central part of Nirad’s lessons is teaching young people how to access, understand and interpret historical and other information.

“They’re all really sharp, especially when it comes to matters of history,” says Nirad. “I used the funding to buy maps which, instead of being navigationally proportional, are territorially proportional. So, instead of Africa being this big,” Nirad gestures, “Africa is this big.” He widens the gap between his hands.

Introducing children to more accurate world maps is crucial for understanding their own histories, as well as the relationship between the rest of the world and the UK which, at one time, was the largest empire to exist in human history.

The near-total absence of colonial history from the national curriculum leaves few opportunities for teachers to acknowledge the legacies of British history and its impact upon young people and the wider world today. A helpful tool for teaching children about these legacies is looking at maps; specifically, how dominant mapping projects to this day exaggerate the size of historically colonial countries near the poles and reduce the size of those near the equator, typically colonised countries. Nirad is also teaching his pupils how to use an atlas.

“We’re going to be learning about Grenada, so they’re finding Grenada and getting familiar with using an atlas because I know, eventually, they’re going to have to do that. It would also be great if they knew how to find a river in the north of England or a place in West Africa when they have fifteen minutes at the end of class without having a teacher prompt them.

As someone who is twelve, you’re not going to remember the ins and outs of the courses of a river but you are going to remember the feeling of how it was to learn about the river and how it was to be with other people. That’s the most important thing. There’s stuff you’re not going to learn at school. You can’t learn everything at school in a capitalist system.”

With funding from Challenge and Change, Nirad has also hosted a session for the Educator strand of No More Exclusions where educators working in university and mainstream Saturday schools came together. He believes it’s crucial to engage teachers in discussions about radical pedagogies within education.

“Ultimately, teachers go through the same education we go through. Racists go through the same education we go through. That’s how they end up. It’s not that they got lost in a sea of ideas. They had the same basic training that we have. So we can’t rely on teachers in the same system to do this stuff, but it doesn’t mean we should abandon them. I always want to work with teachers, ultimately, because they’re people who engage with kids on a day-to-day basis.”

“You have to be involved in something radical if you’re trying to change a situation. If those organisations don’t exist, create them.”

Increasingly, Nirad is finding that collaboration is key. He draws upon the Black radical tradition when considering his place as a young person leading change within a much larger and historic movement to challenge the dominant pedagogy.

“The whole point about the Black radical tradition is it’s not one person, it’s a series of people who found themselves in conditions and responded to them in certain ways, often by drawing on other people. It’s about frameworks that have been created, developed, tested and changed.

In Birmingham, we’ve realised there aren’t really these go-to places that, for example, may exist in Bristol. By holding events in a space, you change a space. Even if it’s slightly. Even if you end up leaving a banner that stays up on the wall.”

To this end, he maintains a good relationship with Gap Arts in Balsall Heath, south Birmingham, where he hosts events for both his work with Maslaha and No More Exclusions. This year, he also organised a teach-out during the National Education Union and University and College Union strikes in March and will be starting the new academic year with a Teachers’ resource exchange.

Nirad is excited by the opening of a new community library, the Nicole Andrews Community Library, in the historically important area of Handsworth, where he can imagine some of his work contributing to the set up of the space.

“It’s a really basic but fun thing to do,” says Nirad. “It shows how easy it is to take a situation that you are directly involved in, so lived experience of the education system, lived experience of miseducation, and then say I’m not going to rely on other people to change something but I can begin to change it in partnership with lots of other people. I know what the end point is and I’m interested in the journey. Otherwise, I’d jump straight to the end.

You have to be involved in something radical if you’re trying to change a situation”, Nirad advises. “If those organisations don’t exist, create them.”

–

If you want to connect with Nirad, you can do so by following him on Twitter.

More information about the work of No More Exclusions can be found here and the work of the Children of the Sun Saturday school here.

–

The Challenge and Change Fund is designed by young changemakers for young changemakers. It funds young people directly, supporting them to create the change they want to see. It prioritises young people who are emergent and have lived experience of the injustices they are trying to change, supporting youth led collectives, social enterprises and CICs across England. You can read more about Challenge and Change here.