In the wake of a parental imprisonment, academic, activist and artist Jemmar Samuels is reclaiming her life and helping other young people like her to do the same.

“Apparently I’m really good at making people understand things,” says Jemmar Samuels, gravely understating how compelling an advocate she is. “I’m a campaigner but I’m also someone who just wants to have a soft life and unfortunately, because of the oppression I experience on a daily basis, I can’t. I’m just fighting to have a soft life that I deserve.”

In 2019, police arrested Jemmar’s stepfather and searched her home. In an instant, life as she knew it was overturned and she quickly discovered that support for children of detained and imprisoned parents does not exist. It is a pain with no end in sight. Like Jemmar, over 300,000 children in the UK have been impacted by parental imprisonment and are separated from their parents by a prison sentence each year. Despite this, there is no statutory framework for identifying and supporting these children.

“My life fell apart in a different way”, she explains. “People say ‘you’ll come through this’ but I know this is actually different. There’s this expectation that I need to figure it out, that I need to power through and it’s like, how do I power through when there’s no structure?”

Following the arrest, Jemmar grew increasingly isolated from her friends during a period in which she feared for her family’s safety. Families of prisoners are at risk of violent retaliation and it is believed that the overwhelming majority of families never tell anyone outside their household that they have a parent in prison.

Most astonishingly, perhaps, is the little-known fact that children can be left alone without care when one, both or their only parent is detained. Like Jemmar, these young people are expected to navigate and be responsible for their parents’ financial and other affairs when they are imprisoned. Most recently, Jemmar has been fielding frequent calls and letters from debt collectors about money owed by her stepfather.

“I say, ‘well, he’s in prison’ and then there’s this confusion because there’s a lack of structure, guidance or policy to refer to when handling this kind of situation and they don’t know what to do. That situation with the debt collectors has been replicated in so many different ways in my personal life and in the lives of my family members: no grace, no understanding.”

“People think only bad people who deserve it come in contact with the criminal justice system and that is not true.”

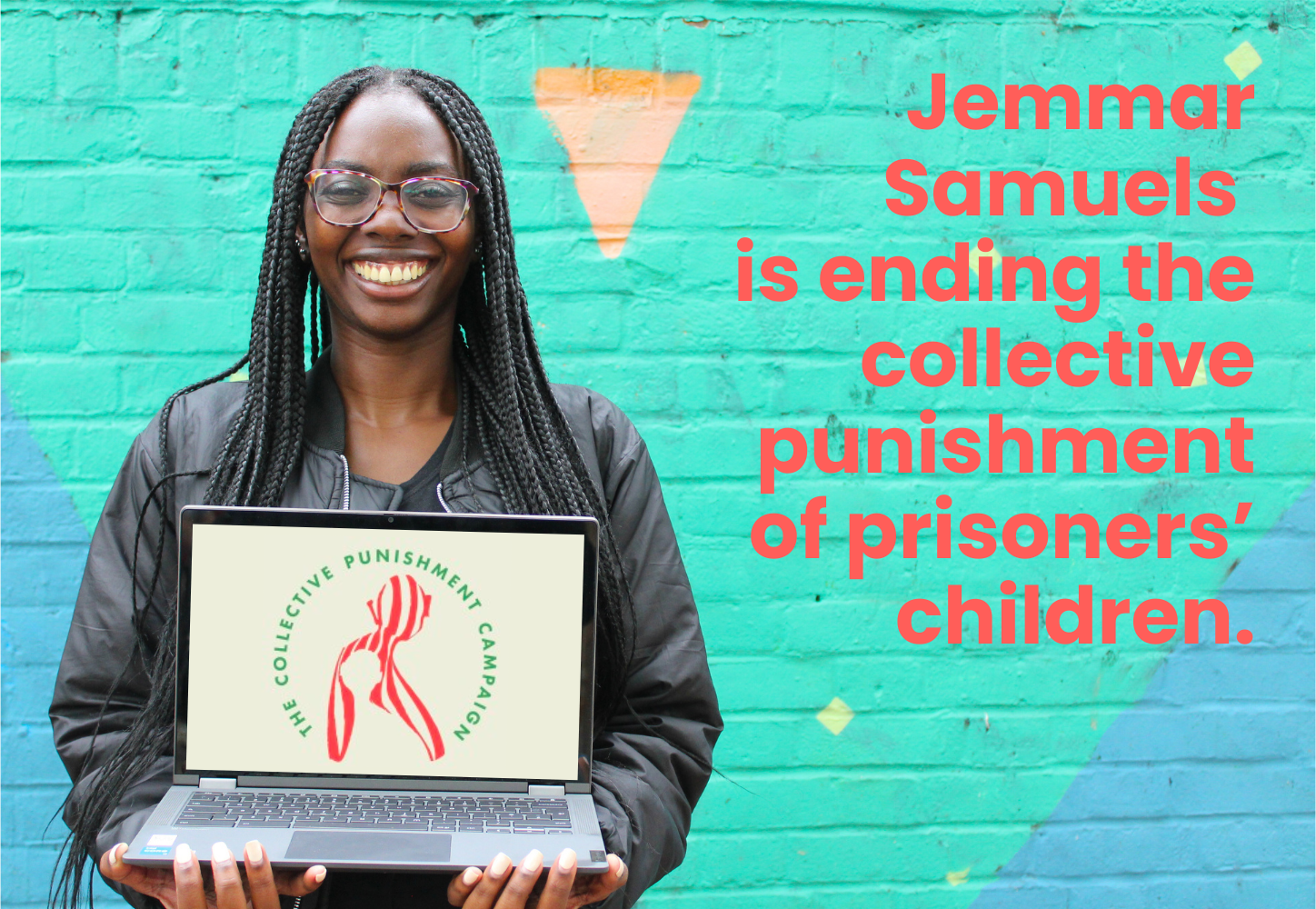

Pictured: Jemmar at a mural of Olive Morris, one of the UK’s greatest community leaders and activists in the feminist, black nationalist and squatters rights campaigns of the 70’s.

One of the charities that worked with Jemmar’s family in the wake of her stepfather’s imprisonment was Children Heard and Seen, to whom Jemmar was connected by a colleague she met during a media and communications internship.

“It changed my sister’s life and it was in the middle of a pandemic”, says Jemmar. “Her dad went to prison, she was in and out of school, the police were coming in and out of the house and questioning her. Children Heard and Seen understand that this is a form of grief. They send us stuff for Valentine’s day and Christmas, and they check in all the time. They even play video games with her. I thought, ‘wow, someone understands my experience.’”

In an attempt to get some clarity about who is responsible for the wellbeing of the families of prisoners, Children Heard and Seen sought answers from the Minister of Justice, who referred them to the Minister of Education who, in turn, referred them to the Children’s Commissioner.

“No one’s responsible for this”, says Jemmar. “It just shows how much they don’t care.”

Nobody knows how many parents are in prison in the UK. Jemmar believes that a lack of information, misinformation and poor public perception of prisoners has allowed the government to evade responsibility for these families for many years.

“People think only bad people who deserve it come in contact with the criminal justice system and that is not true”, she says. “People’s family members have been handcuffed by the police, arrested, abused, their houses destroyed and trashed. People are being arrested and their kids are being left without anyone to take care of them. They’ve been disrespected and criminalised. What happened to being innocent until proven guilty? That’s what’s happening to their families and they’re not even on trial.

There are people doing something about this but these are really nice people who are doing their job. There aren’t many people who have the lived experience to have that personal drive. I have to do this because I can’t function. My family can’t function. We cannot survive and move past this because there’s no guidance. That’s why I applied for this funding. ”

With support from the Challenge and Change Fund, Jemmar launched the Collective Punishment Campaign in September 2022 with the aim of filling the vast void of information and support that families need following a parental imprisonment and raising awareness amongst the general public.

The name of the campaign was inspired by a friend who, after hearing about Jemmar’s situation, suggested that she and her family might be experiencing a form of collective punishment. Commonly, collective punishment is a term used within the context of armed conflicts and humanitarian law, in which an entire group of people are punished for the actions of one or a few individuals. The collective punishment of prisoners’ families, specifically, has a long and well-documented history dating back to ancient Greece.

“If your parent dies, or if your parent leaves your life, that’s seen as sad, but If your parent goes to prison, there’s no grace”, Jemmar explains. “A part of my healing process is minimising this happening to other people. This shouldn’t have happened. Sometimes I don’t sleep. Sometimes I’ll be doing something and I’ll remember that the State does not provide any support for the families of prisoners. My lived experience doesn’t go away. It’s there with me all the time.”

The Fund’s focus on resourcing young people with lived experience was one of the main reasons why Jemmar applied to Challenge and Change for funding.

“Honestly, it felt so satisfying to know that someone believes in this work that I want to do”, she says. “What I love about Blagrave is that there’s no pressure for me to have strict deadlines. Some of the website designing work didn’t get done by a deadline I set and the world didn’t end.

Financially, it’s been a game changer because I’m getting paid to do what I love. It’s the first time I’ve properly been paid for my campaigning work in my life, and I’ve been doing this for about ten years at this point. It’s given me such freedom. I know, once this is done, this is going to be amazing. And I couldn’t have done this without this funding. I hope that funders will be like this in future.”

“Putting a person with lived experience in the room changes the game completely.”

Jemmar appreciates the Fund’s more accessible approach to resourcing young leaders and believes that more funders should embrace lived experience as a form of expertise.

“Putting a person with lived experience in the room changes the game completely”, she says. “I love seeing politicians talk about problems they have no connection to and then you put someone who actually lived that experience in the room and you see the way they start to feel uncomfortable, the way they don’t know what to say. I think working with people with lived experience and funding people with lived experience is a game changer.”

With support from the Fund, Jemmar is building a branded website and accompanying social media campaign that will provide vital information and signposting to families experiencing parental imprisonment and educate the broader public with the aim of influencing policy. She has also been able to pay for a Google Workspace account, graphic designers, a new laptop and, crucially, for her time, which she spends building relationships with others who can support her campaign, including organisations as far away as Glasgow and Birmingham.

Jemmar’s goal is to secure comprehensive policy reforms that will meaningfully end the collective punishment of families and ensure they are adequately supported following a parental imprisonment. She believes that the practical changes that need to happen should, with enough political will, be relatively straightforward to implement. Her campaign doesn’t call on the government to develop and propose any of these reforms.

“We don’t need another report,” she says. “The reports have been done, the research is there by think tanks, charities, CICs and, to some extent, the government, and they all say here are the problems and here are some solutions. But nobody is putting in the time and effort to actually implement them.”

A crucial part of the campaign is ensuring that a permanent role or department is created within the government that is responsible for overseeing the implementation of these policies, which should include a comprehensive package of support for families.

“One thing that I’m considering advocating for is that when a parent is arrested, there’s an opt-in system for families to get support from the government, from the local council. If they’re impacted financially then that means they get vouchers. If they want a social worker then they can get a social worker to support their families. They get told about support groups in their local area that they can get involved in, counselling for the children.”

Jemmar has several ideas about how the campaign will grow. In the immediate future, for example, she plans to collaborate with other organisations and provide expert feedback on the resources they are creating about parental imprisonment.

“If I could be full time doing this work, I would be”, she says, “I wouldn’t have to go and look for another job because I need to earn a certain amount of money to sustain myself and my family. What I need right now is for more people to donate to the campaign. That’s it.”

—

You can donate to the Collective Punishment Campaign on Open Collective here.

You can also connect with the Collective Punishment Campaign on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

—

The Challenge and Change Fund is designed by young changemakers for young changemakers. It funds young people directly, supporting them to create the change they want to see. It prioritises young people who are emergent and have lived experience of the injustices they are trying to change, supporting youth led collectives, social enterprises and CICs across England. You can read more about Challenge and Change here.